As a film scholar, arriving in Tallinn to start my ERC post-doctoral research fellowship entailed not only familiarising myself with the location (the city as well as the buildings of Tallinn University, my current workplace), but also dipping into the local cinema-going culture. Given Tallinn’s renown as the location of one of the A-list film festivals in Eastern Europe, The Black Nights Film Festival PÖFF (taking place as I write this), I was curious to learn more about its movie theatres and their audiences.

Exceptionally during these pandemic times, Estonia still has its movie theatres open. My exploration started with Coca Cola Plaza, a several-floor-high, new building that houses a number of multiplex screens, where I had the opportunity to watch Tenet (Christopher Nolan, 2020). Tenet was eagerly anticipated in Estonia as the film was shot in various parts of Tallinn, which partly explains its extended cinema run and continuous success with local audiences. The Plaza also serves as one of the locations of PÖFF.

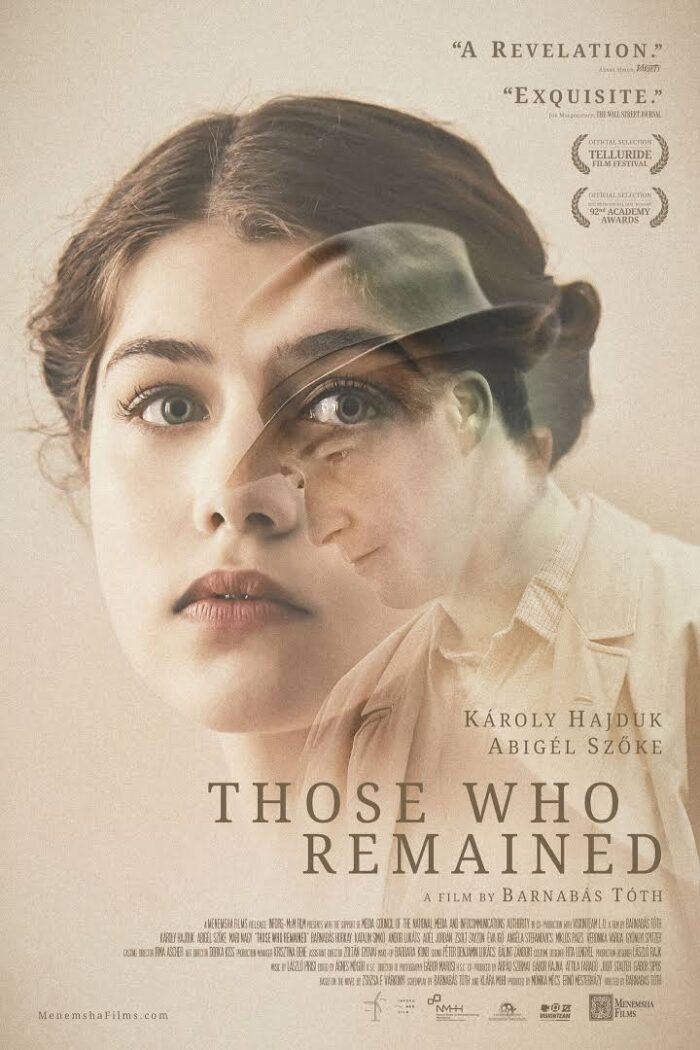

At the other end of the spectrum, Tallinn also has an independent cinema, Sõprus (a word that means friendship in Estonian). Originally built in 1955, the venue has functioned as a cinema since Soviet times. Its grand façade and elaborate interior were commissioned at the height of Stalinism. Since 2010, Sõprus has established its reputation as a contemporary European art-house movie theatre, “famous for its non-mainstream and quirky film selection,” to quote from the theatre’s own website. From among the variety of their programmes, two films were immediately appealing to me. First, a retrospective of Veiko Õunpuu, an Estonian filmmaker whose latest film, Viimased(The Last Ones), was released in 2020. Second, the Hungarian Movie Nights, which ran from September to October 2020. During this event, five films were introduced to the Estonian audience, one film per week, encompassing both classic and more recent productions. Of particular interest to me, and for the research I undertake as part of the “Translating Memories” project, were two films that deal with the Hungarian past. Akik maradtak(Those Who Remained, Barnabás Tóth, 2019) is set in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, and its action covers the period until Stalin’s death, while Foglyok(The Captives, Kristóf Deák, 2019) takes place in 1951. Those Who Remainedwas screened with both Estonian and English subtitles, so we watched it together as a team. The screening was free, and we were also welcomed with a glass of Hungarian wine. As it turned out, the event was organised and sponsored by the Hungarian Cultural Institute in Tallinn.

Hungarian cinema already has an established reputation in the global market, a fact confirmed by the continuous presence and success of Hungarian films at international film festivals, including PÖFF. This year, István Szabó’s latest film, Zárójelentés(Final Report, 2020), has been officially selected in the prestigious competition section of PÖFF. In contrast, this blog entry is the result of the interest in other ways in which Hungarian films, especially historical films, are made available to Estonian audiences outside of both the film festival circuit and the regular distribution channels (theatrical releases). Tamás Orosz, the director of the Hungarian Cultural Institute, kindly agreed to meet and tell me more about the institute’s cultural activities revolving around film. In what follows, I summarise our conversation, emphasising how Hungarian films about the past reach audiences in Estonia.

The Hungarian Cultural Institute is a government agency subordinated to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and plays a significant role in presenting Hungarian culture and language abroad. Every year, around this time of the year, the institute prepares a plan of its cultural activities for the next calendar year, which is then sent to the ministry for approval. As Mr. Orosz pointed out, film represents only one type of cultural activity organised by the institute. For the first time this year, a longer programme, the Hungarian Film Nights, featured alongside the usual one-off screenings of individual films. In view of the films’ role as a mediator between Hungarian and Estonian culture, Mr Orosz emphasised the importance of securing subtitles in Estonian to attract local audiences. Similarly, the free screenings are meant to encourage as large a participation as possible, while the complimentary wine gives a warm, celebratory tone to the event.

When planning the Hungarian Film Nights, the focus was not specifically on historical films but rather on comedy. The Captivesfits the bill due to its underlying absurdist, humorous tone. Those Who Remainedrepresents an obvious departure from the thematic focus. Yet Mr Orosz included the film out of a desire to show not only the latest productions coming from Hungary, but also because it was deemed appropriate in terms of its original timing (April). The film series was planned to take place in spring, with Those Who Remainedto be screened last on April 30th, Hungarian Film Day. The film was officially submitted to the Oscars by Hungary and, if nominated, it could have provided that extra buzz that would have captured a wider local audience.

Those Who Remainedfocuses on teenager Klára Wiener (Abigél Szőke) and middle-aged Dr. Körner Aladár (Károly Hajduk), two Holocaust survivors, and their attempt to forge a connection and heal. The film gives a specific Eastern European flavour to the familiar trope of the near-impossibility of connecting meaningfully in the immediate aftermath of trauma. In addition to a big age difference between the two characters, Those Who Remainedposes another, seemingly insurmountable, challenge directly related to the specific political context of Hungary (and Eastern Europe more generally) in the 1950s: the establishment of a Stalinist-style political authoritarian regime. Both phenomena represent threats to the innocent father-daughter love that could provide the two characters with something meaningful to live for. First, Klára’s teacher stumbles upon the pair, who are spending a sunny afternoon in a Budapest park and are sharing what looks like an intimate, romantic moment: Klára is resting her head in Aldó’s lap, and his hand is gently stroking her hair. Scandalised by what she sees, the teacher attempts to change their living arrangement. By this point in the story, Klára splits her time between her aunt’s and Aldó’s flat, as she is jointly looked after by both. Until this moment, the arrangement seemed to be beneficial to both: Klára finds it easy to talk to Aldó and expresses her guilt at not being able to save her little sister, while Aldó opens up by sharing his pre-war family album with Klára. Second, the specific historico-political context puts a distinctly Eastern European pressure on the situation. One fated night, overwhelmed by the threatened menace of Aldó being disappeared during the political purges of the Rákosi regime, they come close to going beyond their father-daughter love. The film gently navigates these traps in an understated and visually accomplished manner, under the careful direction of Barnabas Toth and with the support of amazing performances by the two leads.

Since 2019, a similar film series has taken place outside of Tallinn, in Tartu. The Hungarian Film Club is organized by Kriszta Tóth, Visiting Lecturer in Hungarian Language at Tartu University. This event is financially supported by the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade through a scheme that was launched in 2019 and specifically targeted at Lectors of Hungarian Language and Culture all over the world. It speaks to Kriszta Tóth’s merit that she chose to propose a film series within this framework. The films selected for screening at the Elektrikteater, an independent cinema in Tartu, show the diversity of Hungarian cinema by including recent international critical successes, such as Saul fia(Son of Saul, Lajos Nemes, 2015), which won an Oscar, and Testről és lélekről(On Body and Soul, Ildikó Enyedi, 2016), the winner of the Golden Bear at the Berlinale, alongside popular films such as the animated film Macskafogó(Cat City, Béla Ternovszky, 1989) and classic (historical) films such as Szerelem(Love, Karoly Makk, 1971). The Hungarian Cultural Institute, albeit not directly involved, helps out by securing the transportation of film copies when necessary and shows support by providing catering and wine on the opening night.

Other events have an ad-hoc character. On occasion, the institute has been approached to support the screening of individual films selected by other institutes, such as the Baltic Film and Media School at Tallinn University. For example, on November 28, 2018, on the occasion of the Day of the Hungarian Gulag Victims, a free screening of Örök tél(Eternal Winter, Attila Szász, 2018) took place in the SuperNova movie theatre at BFM. Similarly, this year, Sőprus Kino initiated the screening of Béla Tarr’s cultic 7-hour-and-19-minute Sátántango / Satan’s Tango (1994). On such occasions, the Institute provides the copy of the film and covers the cost of the screening license.

In 2018, two films representing women’s experiences of the historical past were screened as part of the Visegrád 4 Film Days, a two-day event celebrating the Hungarian presidency of the Visegrád Group, a cultural and political alliance of the four countries of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. The two films are Anyám és más futóbolondok a családból(Mom and Other Loonies in Our Family, Ibolya Fekete, 2015) and Aurora Borealis (Márta Mészaros, 2017). The significance of these films in relation to the historical past cannot be overstated.

By way of ending, it is worth noting that, at the level of cultural diplomacy, the view is that cultural production dealing with the Hungarian past is easily accessible to Estonians due to a shared, common past. Tamás Orosz remembers that one of the people he first met when he arrived in Tallinn, Tiit Aleksejev, the president of the Estonian Writers Union since 2016, suggested investing in literary translations of novels that focus on historical events, a terrain where the similarities with the Estonian past are palpable. One can only hope that not only such books but also films appeal to a wider Estonian audience, and, judging by the audience present at the screening, there is definitely a potential there.